The historical record

Who Built the Dams?

Various dams were built in the Columbus area along a two and a half mile stretch of the Chattahoochee River due to a drop in elevation of 124 feet. This drop in elevation is due to the river crossing the lower piedmont hills before meeting the flat coastal plain. This transition from the piedmont to the coastal plain is called the Fall Line and creates a tremendous potential for water powered industries such as grist mills, saw mills, and textile mills.

The Federal Government was aware of the possibilities for water power at the Falls of the Chattahoochee and in 1827 ordered the Corps of Engineers to survey the Columbus area as a possible site for a Federal Arsenal. The ensuing proposal projected an approximate cost of $1,260 per year to ship goods and raw materials to Columbus compared to $367.50 for Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The cost factor prevailed and Columbus was not chosen.

In 1828 Seaborn Jones built the first wooden dam along the falls of the Chattahoochee North of the City of Columbus. This dam was a weir, or wing dam, extending out into the river only far enough to channel water into the grist mill. The water provided the power necessary to turn the water wheel that was connected to the grinding stones. Local farmers brought their wheat and corn to Seaborn Jones’ mill to be ground into flour and corn meal. Today this mill is known as City Mills.

The Water Lot Company

In an effort to attract industry to the city of Columbus in the early 1840s, a decision was made by city leaders to place industrial development along the Falls of the Chattahoochee into the hands of private enterprise. Thirty seven water lots were laid out in preparation for selling them at a low rate to investors. John H. Howard and Josephus Echols quickly purchased all even numbered lots and soon thereafter they purchased lot number one. The primary stipulation in their deal with the city of Columbus was that they were tasked with constructing a dam and headrace to supply water and thus power to the water lots. The goal was to entice other businessmen to locate industry on the Chattahoochee in Columbus. By 1843 Howard and Echols had purchased the remaining odd numbered lots and therefore effectively maintained a monopoly over the power generated by the rapids at Coweta Falls.

Instead of completing a raceway all the way to lot 37, as originally specified, the raceway probably was never constructed any further than water lot 14. By 1845 the water lot dam was complete and a textile mill, Coweta Falls Factory, had been built and was in operation just below the dam on water lot 1.

The system Columbus had in place for developing industry along the Chattahoochee River was quite different than the methods some other Georgia cities employed. Columbus leaders decided to let private entrepreneurs handle the building and maintenance of the dams and selling of the water lots, whereas in Augusta, Georgia a canal was built in 1845 and maintained by the city. The Augusta Canal provided water power, transportation and water for the Augusta Water Works. Various companies, including textile industries, leased water power from the Augusta Canal Company in order to power their mills. This ensured more thorough maintenance and a more constant supply of power verses a privately owned and maintained dam as seen in Columbus.

The Businessmen

An early settler to the Columbus area was Seaborn Jones, who moved in 1827 to the newly settled town from Milledgeville, Georgia at about the same time as his brother in law, John H. Howard. Jones began a mill on the Chattahoochee River situated where City Mills is currently located. The dam he constructed to power his grist mill was the first one in the river at the Great Falls. Like most other successful men of his time, Jones wore many hats, including his occupation as an attorney, representing Georgia in Congress, and of course grist mill owner.

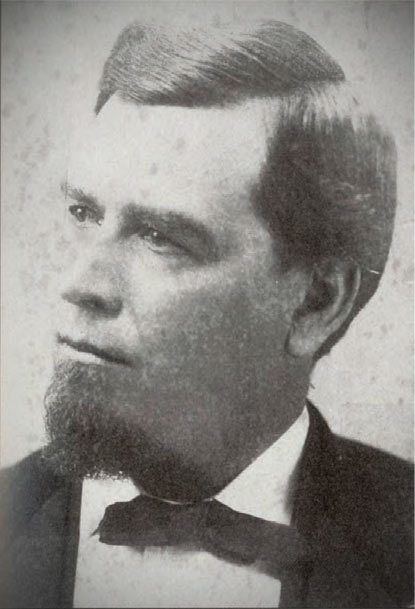

Seaborn Jones

Seaborn Jones. Courtesy Georgia Department of Archives and History.

Born February 1, 1788, Jones married Mary Howard (1788-1869) in 1810, a sister of John H. Howard. After attending Princeton College, he was admitted to the bar in 1808 and set up practice in Milledgeville, Georgia. He served as the Solicitor General of the Ocmulgee Circuit in 1817 and Solicitor General of Georgia in 1823. In 1825 Jones served as an aide to Governor George Troup and was the master of ceremonies for General Marquis de LaFayette’s visit to Georgia in March of 1825. Lafayette came to America to help fight the British in the American Revolution. He was not yet 20 years old when General George Washington made him a member of his staff. Lafayette would eventually command Continental Army troops in several important battles. In 1824 General Lafayette was invited to the United States to visit all 24 states as a returning hero. In Savannah, Georgia he laid cornerstones for monuments to General Nathaniel Greene and to Count Casimir Pulaski. Count Pulaski was killed in the Battle of Savannah. After the celebrations in Savannah, Lafayette travelled to the towns of Augusta, Warrenton, Sparta, Milledgeville (the capital) and Macon. After leaving Macon, Seaborn Jones escorted Lafayette and his entourage to the banks of the Chattahoochee River just south of the area that would later become Columbus, Georgia. General Lafayette and his staff were ferried across the river to Fort Mitchell, the first stop on his tour of Alabama. Jones was also commissioned to visit the Coweta Reserve to investigate Indian affairs and conflicts arising in the Creek Nation. These visits sparked his interest in the Columbus area.

In 1827 he moved his family to the newly settled town of Columbus, Georgia. Jones constructed a grist mill in 1828 along with a wing dam into the river that did not extend all the way across. The simple dam utilized the rock islands already in existence to force water to his grist mill to supply water power for the grinding stones. Because he was an active attorney, it is likely that Jones leased the mill to others. He certainly leased the mill to Jonathan Bridges around 1839 until the 1850s. In 1831 he partnered with Dr. Stephen Miles Ingersoll to open a ferry one mile south of town. Due to the development taking place farther north into Columbus; the ferry was not very successful. In 1833 Jones completed construction on the family home, which he named El Dorado (later named St. Elmo), a beautiful home which still stands today. Jones was elected to Congress in 1833 and again in 1845.

Southern Research staff member at Seaborn Jones' burial, Columbus Georgia.

He and Mary had at least six children, only two of which survived to adulthood. Their only surviving son, John A. Jones, was killed at the Battle of Gettysburg at Little Round Top. Their daughter, Mary, married General Henry Lewis Benning in 1838. Seaborn, who passed away March 18, 1864, and his wife, Mary, are buried in a plot alongside their daughter and son-in-law at historic Linwood Cemetery in Columbus, Georgia.

Dr. Stephen M. Ingersoll

Dr. Stephen Miles Ingersoll. Courtesy Columbus Museum.

Dr. Stephen Miles Ingersoll was born in Duchess County, New York on March 15, 1792 to Stephen and Sara Ingersoll. Dr. Ingersoll would become an influential businessman in the Columbus, Georgia and Phenix City, Alabama area. After studying to become a physician, Dr. Ingersoll served in the War of 1812 before moving south in the 1820s. He spent some time prospecting for gold in North Georgia, then moved to Bibb County and served in the Georgia legislature. He moved his family to the Columbus area as the city was first being settled, set up a trading post, and quickly made friends with the Indians in the vicinity. Dr. Ingersoll was involved with helping to lay out the town of Columbus and partnered with Seaborn Jones to establish a ferry at the southern portion of the town.

By 1832 Dr. Ingersoll had settled across the Chattahoochee River from Columbus in Girard, AL (later became Phenix City, Alabama). He built a home for his family on a hill overlooking the river that later became known as Ingersoll Hill and continued his trading post operations. As early as 1839 Ingersoll began operating a saw mill on the river. He situated the mill so close to the water’s edge that one of the mill’s support posts rested in the riverbed. He reportedly had to blast rock in the river bed to make room for the mill’s water wheel. Upstream from the mill he constructed a wing dam in the river running in a north-east direction to direct water toward the mill. Rock had been blasted from the riverbed to make room for the water wheel.

Legend has it that Dr. Ingersoll was the true creator of the “Morse Code”, a communication system he used on his plantation. The man credited for inventing the Morse Code, Samuel F. B. Morse, allegedly accompanied a friend to Dr. Ingersoll’s plantation and observed the communication system in place. A newspaper quoted Morse as acknowledging the idea for the telegraph communication system came to him after visiting a southern doctor.

When John H. Howard and Josephus Echols built a dam downstream in the river in 1845, as requested by the city of Columbus, it forced water to back up causing Ingersoll's mill equipment to become inoperable. Ingersoll’s mill was built between the high and low water levels of the river. Ingersoll’s mill was built between the high and low water levels of the river. In 1848 Stephen Ingersoll sued Howard and Echols in the Alabama Circuit Court and was awarded $4,000 in damages. However, Howard and Echols quickly countersued and eventually the case went to the United States Supreme Court, leading to a landmark decision in 1852 establishing riparian water rights. The Supreme Court ruled in favor of Howard and Echols deciding that Georgia owned the Chattahoochee River up to the high water mark on the Alabama side. This case effectively prevented water power industry from developing on the Alabama side of the river.

Dr. Ingersoll would later become a director of the Girard Railroad and he also donated land for the construction of an Academy near his family home. William H. Young purchased Alabama land from Dr. Ingersoll during the Civil War to establish housing for his Eagle and Phenix mill workers. During the Civil War, the mill town of Browneville, which was previously a field belonging to Dr. Ingersoll, was built for Eagle and Phenix workers. It included schools, churches, lodges, and stores.

Stephen Miles Ingersoll's burial, Columbus Georgia.

Dr. Stephen Miles Ingersoll was a pioneer settler in the Columbus area, quickly establishing positive ties to the Native American Indians there. Due to his friendship with the Indians, he was one of the first white settlers in the current day Phenix City, Alabama area. He served as a physician to his community, provided a place for education, and challenged the powerful businessmen in Columbus over rights to the power the river offered. He died June 5, 1872 in Browneville, Alabama and is buried beside his son, Dr. William Jackson Ingersoll, in the historic Linwood Cemetery in Columbus, Georgia.

William H. Young

William H. Young

William H. Young was born January 22, 1807 in New York City. He proved to be an excellent businessman early in his life and would eventually be labeled the “Father of Cotton Manufacturing in the South”. In the spring of 1824, seventeen year old Young moved to Twiggs County, Georgia where he worked as a clerk serving Mr. Ira Peck. After a year of this work, his older brother Edward B. Young, joined him and they went into business together. Their partnership would last upwards of 10 years, ending when Edward moved to Alabama to begin new business ventures. William went back to New York but quickly decided he preferred living in the Southern states. In 1834 William H. Young married Ellen Augusta Beall from Warren County, Georgia. She was from a prominent family, her father having been handpicked by the Governor to supervise the Georgia land lottery. The couple had at least six sons, three of which served in the Civil War, one dying at the Battle of Marietta, Georgia. One son, Alexander C., graduated from the University of Georgia in 1870 and returned to Columbus to help his father in the textile industry, while others ventured into farming.

In 1839 he made Apalachicola, Florida his home and maintained a successful insurance business (Apalachicola Mutual Insurance Company) there for about fifteen years. However, William had kept his sights on the Columbus, Georgia area for many years. He had visited the area in 1827 while he was living in Twiggs County but at that time the Indians were just leaving the area and little, outside of surveying, had been done. There were no established roads in the area just yet and in order for William to see the Falls of the Chattahoochee, he had to cross the river into Alabama, travel upstream via the Government Road, then cross again. Legend has it that he stood on the very site of the future Eagle and Phenix Manufacturing Company and declared that he would someday return and take advantage of the river’s power. He also knew that the fertile lands that surrounded him were perfect for growing cotton and he envisioned the future of textile manufacturing in Columbus. Unfortunately, at that particular time the young William did not have the financial means to put his plan into action; however, that would change in the years to come.

William had not been the only one eyeing a spot at the Great Falls. By the time he began construction on the Eagle Manufacturing Company in 1851, at least three other textile mills were operating in Columbus, along with several grist mills and Variety Mills, a wooden-ware factory. None of these mills would see the success of William’s mill. The Eagle Manufacturing Company advertised in 1851 as needing 200 operatives. These men, women, and children would receive good wages as well as housing free of rent. The company also wanted wool and vowed to pay the highest cash prices around. At that time they produced sheets, shirts, osnaburgs, yarns, jeans, mattresses, and comforters.

Finally in 1855 William moved his family from Apalachicola to the growing city of Columbus. Even though he was busy venturing into the textile industry, he also became President of a bank being organized for the city. He occupied the position of President at the bank until the Civil War during which time the Eagle Mill began running twenty-four hours a day in order to provide the Confederacy with much needed materials. Due to the demands generated by the war, he resigned his position at the bank to focus on the mill full time.

In time, most of his competitors along the Chattahoochee would fail or in the case of the wooden-ware factory, burn, and William would purchase their interests. This was the case with the Howard Manufacturing Company, which failed and was purchased by the Eagle Manufacturing Company in 1860. William H. Young ran such an efficient business that the Eagle Manufacturing Company never accrued any debt and rewarded its stockholders handsomely. In 1864 the Eagle Manufacturing Company opened a free school for underprivileged children.

Federal troops descended upon Columbus in the spring of 1865, burning the Eagle Mills and their cotton supply. Ever the aggressive businessman, William H. Young and stockholders of the Eagle Manufacturing Company reorganized, rebuilt and named the new enterprise Eagle and Phenix Manufacturing Company. Phenix was added to the company name to signify its rising from the ashes. Once again, William prevailed and went on to prosper with the new mill. Eagle and Phenix Mill #1 opened in 1867, Mill #2 in 1871, and Mill #3 in 1879. In 1880 the Eagle and Phenix Manufacturing Company was by far the largest employer in Columbus, employing 213 children, 555 men, and 917 women. The second in numbers was the Columbus Iron works, with 157 workers, all of which were men. Eventually Young purchased all the upper water lots, with the exception of water lot 1, and was, therefore, able to expand his textile operations by building more mill structures and improving the dam and raceway system.

William H. Young & wife burials

William H. Young had a reputation for being an aggressive entrepreneur: perhaps this is one reason he was so successful. As a motivated young man, he had a vision of guiding a successful business at the Great Falls of the Chattahoochee and made this dream become reality. William, his wife, and at least one son are buried in the historic Linwood Cemetery in Columbus, Georgia. Some of the Eagle and Phenix mill buildings still stand today, owned by the W.C. Bradley Company, and have been nicely renovated into condominiums.

John H. Howard

John H. Howard's grave

In an 1874 book chronicling the history of Columbus, John H. Howard is listed as one of the pioneer settlers of Columbus. John Harrison Howard was born in 1792 in Elbert County, Georgia to Major John Howard and Jane Vivian Brock Howard. At only 15 years of age, Major Howard served in the Revolutionary War and as a result of this he registered for the 1805 Georgia Land Lottery. From the lottery he received property in Milledgeville, Georgia. Major Howard became a wealthy planter and father to at least nine children, one of which was John Harrison Howard. John H. graduated law school in 1811 and in 1818 married Caroline Matilda Bostick. The couple moved from Milledgeville to Columbus shortly after the birth of their first child. John H. and Caroline would eventually become parents to ten children. John H.’s sister, Mary Howard, married another early prominent settler to Columbus, Seaborn Jones. Another sister, Sarah, was the mother of the famous author, Augusta Jane Evans.

Howard served many roles in his lifetime which included serving as the head of State troops during the Creek Indian War of 1836, serving as President of the Mobile and Girard Railroad, and forming the Water Lot Company of Columbus, Georgia with business partner Josephus Echols in 1845. Howard and Echols began their textile manufacturing career in 1841 by purchasing the newly formed water lots from the City of Columbus and taking on the task of building a dam and raceway, which would in turn attract more industry at the Great Falls of the Chattahoochee. Eventually the two men would own all of the water lots and later become embroiled in a battle with Dr. Stephen Miles Ingersoll over rights to the river’s water. Dr. Ingersoll owned a mill upstream on the Alabama side of the river and the construction of the Water Lots dam raised the water level enough to render his mill virtually useless. This battle would go all the way to the United States Supreme Court and it became a landmark case in which Georgia was awarded riparian rights to the Chattahoochee River all the way to the high watermark on the Alabama bank.

An article featured in the Columbus Ledger-Enquirer in 1862 honors Howard after his death. The article boasts that Howard, who died at his plantation which was near the Flint River, was so successful in life that “he never knew what it was to fail”. John Harrison Howard and his wife, Caroline, are buried in the historic Linwood Cemetery in Columbus, Georgia.

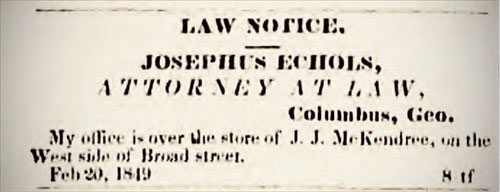

Josephus Echols

Josephus Echols newspaper advertisement

Josephus Echols was a successful attorney and business partner to John H. Howard in the city of Columbus, Georgia. Echols was born around 1807 in Virginia and was serving the Columbus area as an attorney by at least 1835. The Columbus Enquirer printed a notice in June 1835 of a committee planning a celebration of American Independence and noted that Josephus Echols was serving on the ‘Committee to Prepare Toasts’. In 1841 Echols partnered with Howard to purchase water lots at the falls of the Chattahoochee River in Columbus. They would construct the first dam to provide water power to the water lots and hopefully attract prospective mill builders. Eventually the two men would own all of the water lots and find themselves in a battle with Dr. Stephen Miles Ingersoll over rights to the river’s water.

In 1845 Echols was named a Justice of the Inferior Court for Columbus. In 1846 the Columbus Enquirer advertised that Josephus Echols was entered into an upcoming election for Alderman for the 3rd ward. Echols advertised his law practice in the newspaper as well, noting in 1849 that his office was located on Broad Street above J.J. McKendree’s store.

Echols was repeatedly recognized in the Journal of the Franklin Institute for various inventions and improvements upon inventions. A patent for a steam boiler water feeder was obtained by Echols in 1841. In 1846 he was recognized for his invention of a compensating propeller and in 1847 for a steam engine air pump and steam boiler water indicator. In 1855 he made improvements to water gauges for steam boilers, and in 1856 he made improvements to stone drilling machines. There is no doubt that his many inventions helped to advance technologies within the many mills located in Columbus, as well as elsewhere.

On October 12, 1863 Josephus Echols married Rowena Malvena Lockhart (1822-1866) and there is no indication the couple ever had children. Eventually the couple moved across the Chattahoochee River into Russell County, Alabama. Josephus Echols died at 58 years old and his last will and testament left his entire estate to his wife, Rowena. Mrs. Echols’ last will and testament was a bit more specific as she leaves 12 to 14 slaves to each of her sisters, two-thirds interest in the water lots along the Chattahoochee River to her mother, Mary Ann Lockhart, and brother, Robert B. Lockhart. She also left two-thirds interest in patent rights and inventions of her late husband to her sisters, brother, mother, nieces, and nephews. To one niece in particular, Mary J. Thomas, she left six shares of Eagle Factory stock as well as 50 slaves and the rest of the estate. The will states that the Echols had property in Alabama and Georgia. Josephus and Rowena Echols are buried in the historic Linwood Cemetery in Columbus, Georgia.

John Hill

John Hill

Civil and Mechanical Engineer John Hill was born in 1839 in New Salem, Illinois to Samuel and Parthena (Nance) Hill. Hill took over his father’s woolen mill when he died and when that mill burned he began to manage the Home Manufacturing Company of Jacksonville, Illinois. He came to Columbus, Georgia in 1872 to serve the Eagle and Phenix Mills as Superintendent of the woolen department and later as Mechanical Engineer. While working for the Eagle and Phenix Mills, Hill oversaw the construction of the principal buildings, introduced electric lighting to the mills, and engineered the 1882 stone masonry dam. This dam was a tremendous accomplishment. The previous wooden dams needed constant repair and did not hold up under floods as well as the stone dam. The more sturdy stone dam constructed under Hill’s direction provided a dependable water supply for the mills. He was well known as a mill expert in the Southeast, some referring to him as a pioneer in the cotton milling industry.

While testifying before Congress in 1883 regarding labor relations, Hill insisted that workers performing the same tasks were paid the same rates regardless of race. He stated that all workers were treated equally and worked in a harmonious atmosphere. When questioned about child labor in his mills, he told Congressional members that the children working in the mills were usually not younger than ten. Education, he said, was of secondary importance to southern families. Even if families wanted to send their children to school, the devastating effects from the Civil War were so bad that families needed the income their children could bring into the home. A typical workday for mill workers at that time consisted of 11 to 12 hours. In 1887 an entrepreneur looking to build a cotton mill in Montgomery, Alabama requested the opinion of Hill, who was considered one of the best engineers in the south. Hill thought the mill would be a good idea and urged the builder to employ women and children. The Eagle Manufacturing Company established a free school for poor children in 1864 and public schools were available by 1867.

John and Lula Hill's grave

In 1885, Hill patented his invention for an automatic sprinkler system for the large rooms in the mill. Fire was an ever present danger in textile mills. He continued to make improvements upon his original invention. Hill served as an Engineer for the John P. King Mills in Augusta, Georgia and also maintained his own business, known as Hill Automatic Sprinkling Company. In 1890 he joined William Neracher to form the Neracher & Hill Sprinkling Company, which was eventually sold to the General Fire Extinguisher Company.

John Hill married Lula Clara Crawley and they had four children, two of which would follow in his footsteps as engineers. John continued his work for Eagle and Phenix Mills until 1892 and passed away in 1898. He and his wife are buried in the historic Linwood Cemetery in Columbus, Georgia.

The Laborers

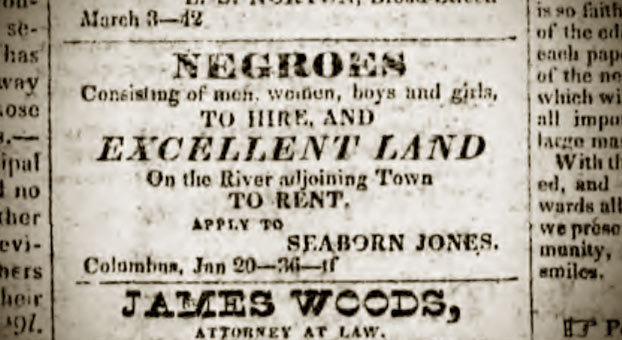

While successful businessmen funded and designed the dams at the Great Falls of the Chattahoochee River in Columbus, Georgia, it is not likely that they physically aided in their construction. Labor for building the dams would have likely evolved from slave labor for the earliest dams to local white and African American men for the later dams. Seaborn Jones owned quite a few slaves in Muscogee County. According the 1830 United States Census, Jones owned 58 slaves, 25 of those were between the ages 10 and 55 and would have been physically capable of providing labor for his mill and dam construction. By 1840 the number of Jones’ slaves increased to 89, 34 of those being males between the ages of 10 and 55. In 1850 he had 56 slaves, 34 of which were males between the ages of 10 and 55. According to the census, John H. Howard owned 29 slaves in 1830, 12 being 10 to 55 years of age, and in 1840 he had 21 slaves, five of which were males between the ages of 10 and 35 (he had no male slaves over 35 years of age in 1840).

March 10, 1832, Columbus Enquirer

Keep in mind the total population for Muscogee County in 1830 was 3,508 with 1,240 of those being slaves. In 1840 the total population was 11,699 and of those people, 4,701 were enslaved. By 1850 the total population had increased to 18,578 with 8,156 of that number being slaves. The total population in 1860 was 16,584 and 7,445 of those were slaves. The slaves that these men owned would not have been the only slaves used for constructing the mills and dams in Columbus. It was common for slave owners to “rent” their slaves out for labor, especially when things were slow on the plantation. It is quite possible nearby slave owners allowed their slaves to aid in the construction of the dams and mills that date before the end of slavery in 1865. The owners would have collected money for allowing the use of their slaves.

These numbers are given to bring awareness to the fact that many slaves were skilled and available in the Columbus area and it is extremely likely that some of them were used to help build structures such as houses and mills as well as the dams. At City Mills, dams were constructed beginning in 1828, then a larger one in 1850, both of which could have been built by the hands of slaves. Near the Eagle and Phenix Mill, construction of the 1844 and 1856 dams was almost certainly assisted by slaves. Most likely there were locals that also helped in the construction of the dams. There would have been free blacks and whites that were skilled in construction and looking for employment.

Before being rebuilt and named the Eagle and Phenix, the Eagle Manufacturing Company advertised as early as 1852 as needing operatives and offered housing as an incentive. Eventually the textile giant offered many other amenities including schools, churches, recreation, lodges, and stores. These tactics helped to keep a committed labor force.

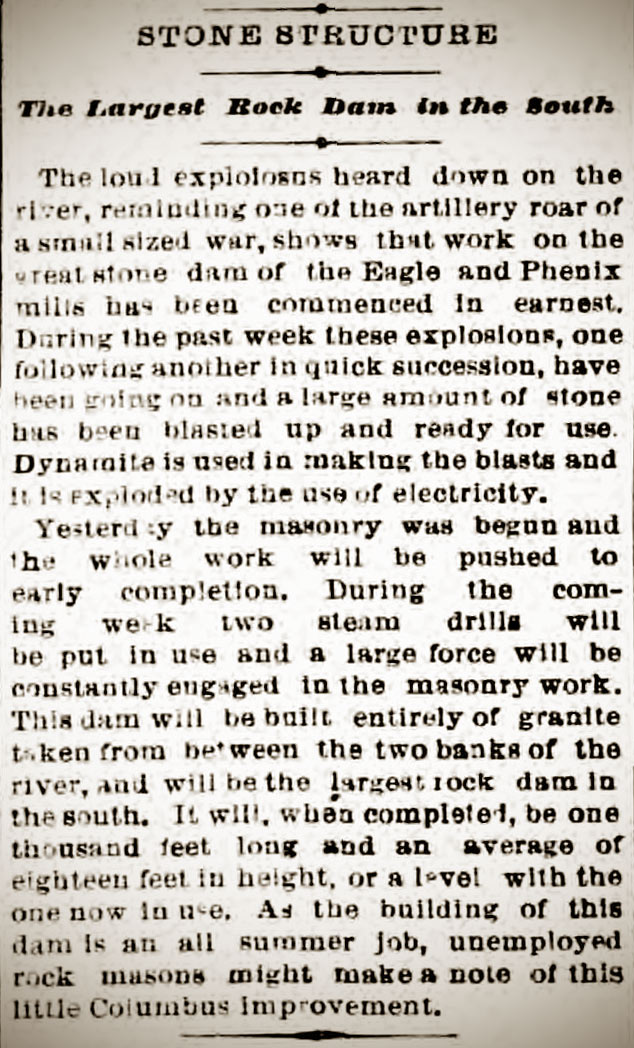

Much excitement surrounded the construction of the 1882 stone dam at the Eagle and Phenix Mill. The local newspaper, the Columbus Sunday Inquirer, documented the building process and dubbed it “The Largest Rock Dam in the South” in one article featured in June 1882. The article discusses the loud explosions that could be heard coming from the construction site as stone was blasted from the river bed to be used in the dam. Two steam drills were used and a “large force will be constantly engaged in the masonry work.” Rock masons in the area were urged to seek employment with the massive undertaking.

Columbus Enquirer article describing the construction of the rock dam

Another Columbus Sunday Inquirer article features an interview with John Hill regarding dynamite. It opens with about a dozen “negro men” rushing away from a man approaching with dynamite in hand while smoking a cigar. Hill told the reporter that there was no danger in the cigar lighting the dynamite as it is ignited by concussion.

A May 14, 1882 newspaper article tells of a near death experience of D.W. Champayne, the superintendent of dam construction and Eagle and Phenix master mechanic, and William Martin, a “colored employee”. The two were in a boat near the center of the river when the wind blew them over the dam, tangling them within the 20 foot waterfall. Both men survived the frightful experience.

The Columbus Sunday Enquirer reported in November 1882 that the building of the dam had been very welcomed by many laborers. Throughout the summer only about 100 workers per day were employed due to the excessive rain and high waters that interfered with construction. However, in the fall the rains ceased and the river bed dried up sufficiently that construction could begin in earnest. After the first part of October 1882, as many as 250 men were employed on any given day and received incentive wages during the stone dam construction.

The 1907 stone masonry dam at City Mills was completed by the Hardaway Company of Columbus, Georgia. The construction of this dam did not receive quite the attention as did the 1882 Eagle and Phenix dam. However, this was a welcomed improvement for City Mills as the wooden dams required constant repairs and faced damage repeatedly from floods.

Sources, links and notes

- www.augustacanal.com

- Columbus Enquirer, April 20, 1852, page 4

- Columbus Enquirer-Sun, August 3, 1887, page 1

- Columbus Enquirer, October 23, 1835, page 1 – Echol’s advertisement as attorney in Columbus

- Columbus Enquirer, May 18, 1852, page 3

- Columbus Enquirer, October 28, 1851, page 3

- Columbus Enquirer – March 10, 1832, page 3 “Negroes… to Hire, Seaborn Jones”

- Columbus Sunday Enquirer – November 26, 1882, page 3 “The Biggest in the South”

- Columbus Sunday Enquirer – May 14, 1882, page 3 “An Awful Accident”

- Columbus Sunday Enquirer – June 11, 1882, page 3 “Dynamite, A Chat with a Gentleman Who Handles It”

- Columbus Sunday Enquirer – June 11, 1882, page 3 “Stone Structure, The Largest Rock Dam in the South”

- William H. Young:

- Photo and most information: Biographical Souvenir of the States of Georgia and Florida. Reproduced. Originally published 1889 – F.A. Battey & Co. Chicago. Photo page 817.

- http://books.google.com/books?id=xO4xAQAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=biographical+souvenir+of+the+states+of+georgia+and+florida&hl=en&sa=X&ei=_BL2U62EOo6fyATbsYGgBw&ved=0CD0Q6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=william%20h.%20young&f=false

- Fifth Session of the Acts and Resolutions of the General Assembly of Florida. 1851. Office of the Floridian and Journal. Printed by Charles E. Dyke

- http://books.google.com/books?id=FAM4AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA26&lpg=PA26&dq=william+h.+young+apalachicola,+florida&source=bl&ots=Hck05qzqT2&sig=wIGJ7_4vjtb8_ATmUzeDWUb89jQ&hl=en&sa=X&ei=nBD2U-LCAcSsyAT7v4KICQ&ved=0CCgQ6AEwAg#v=onepage&q=william%20h.%20young%20apalachicola%2C%20florida&f=false

- HAER documentation, Eagle and Phenix Mills. John S. Lupold, Barbara A. Kimmelman, J. B. Karfunckle. 1977

- http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=8252557

- Columbus Georgia from its Selection as a Trading Town in 1827 to its Partial Destruction by Wilson’s Raid in 1865. John H. Martin. Published by Thomas Gilbert Book Printer and Binder, Columbus, GA. 1874

- Seaborn Jones:

- Knight, Lucian Lamar. Georgia’s Landmarks, Memorials, and Legends, Volume 1 Part 2. Pelican Publishing company, Inc. Louisiana. 1913

- Fidler, William Perry. Augusta Evans Wilson, 1835-1909. University of Alabama Press. 1951.

- A Biographical Congressional Directory 1774-1911. United States Government Printing Office.

- Columbus State University Archives

- Photo: Courtesy, Georgia Archives, Small Print Collection, spc03-016 (this is how they like to be credited)

- John Hill:

- http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GSln=Hill&GSiman=1&GScid=35015&GRid=88624644&

- Philo History: Chronicles and Biographies of the Philosophian Literary Society of McKendree College. Edited by Paul and Chester Farthing. Lebanon, Illinois, 1911.

- Dana, Gorham. Automatic Sprinkler Protection. Published by Thomas Groom & Co., Inc. Boston. 1914.

- Nance, George W. The Nance Memorial, A History of the Nance Family in General. J.E. Burke & Company Printers. 1904

- John Hill, Testimony on Southern Textile Industry, 1883. http://cwx.prenhall.com/bookbind/pubbooks/goldfield2/medialib/chapter19/19.htm

- John H. Howard:

- Knight, Lucian Lamar. Georgia’s Landmarks, Memorials, and Legends, Volume 1 Part 2. Pelican Publishing company, Inc. Louisiana. 1913

- Martin, John H. Columbus, Georgia, From its Selection as a Trading Town in 1827 to its Partial Destruction by Wilson’s Raid in 1865.

- Lyles, John. Images of America: Phenix City. Arcadia Publishing. Charleston, South Carolina. 2010

- http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=34075329&ref=acom

- Columbus Ledger-Enquirer article from 1862 (this is an article someone posted online, I don’t have the specific issue).

- www.ancestry.com

- www.usgennet.org

- Fidler, William Perry. Augusta Evans Wilson, 1835-1909. University of Alabama Press. 1951.

- Josephus Echols:

- The American Repertory of Arts, Sciences, and Manufactures, Vol. IV. 1842. Edited by James J. Maples. Published by W. A. Cox Mechanics’ Institute, City Hall.

- Journal of the Franklin Institute. Edited by John P. Frazer. 3rd Series, Volume XXXI. 1856.

- Columbus Enquirer

- www.ancestry.com

- http://www.google.com/patents/US2212

- House Documents, Volume 30. By USA House of Representatives

- Stephen Ingersoll

- www.ancestry.com

- Linwood Legacy, Volume 9, February 2006, No. 3

- Howard & Echols v. Ingersoll 1851